The inspiration for this project came from my experience at Boiler Room NYC 2024. One of the most incredible moments of the night was during Yaeji’s set, when she incorporated the Mii Theme Song in her performance. The moment of surprise when everyone in the room recognized the familiar yet out-of-place song was ecstatic, and the energy became incredible.

After reading David Huron’s “Sweet Anticipation,” I came to recognize this moment as a shock to “conscious” expectation, specifically to expectations regarding the event and environment, implemented via “veridical” memory, or memory of a specific work. From this, I speculated that DJing as an artform utilizes familiarity with other works more than any other, heavily leveraging our veridical expectations to create anticipation and surprise.

It occurred to me that there was an opportunity to investigate and validate this idea; many DJ sets are posted online by event hosts like Boiler Room, Book Club Radio, and Hör Berlin. The video and audio of these sets could be analyzed, and hopefully some of these ideas could be validated with data. As such, I began developing a tool for analyzing DJ sets.

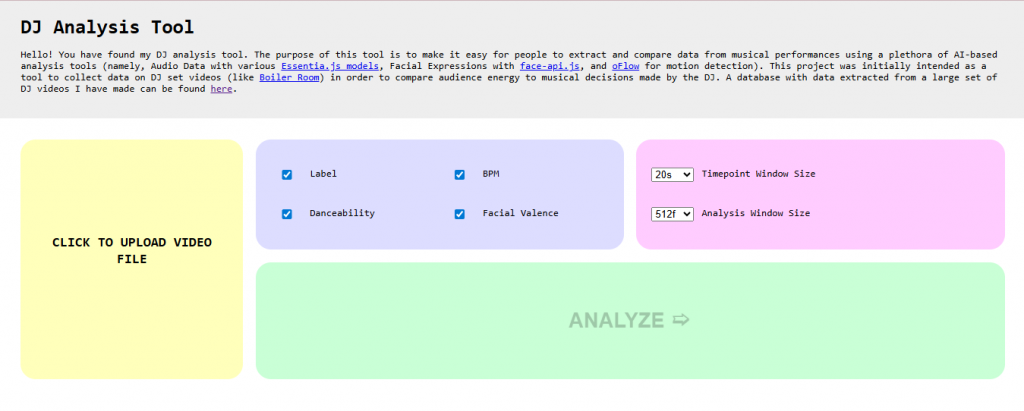

I decided to build a web-based tool so that others might be able to utilize this technology and contribute to the body of analysis without any technical background. Additionally, in my research I found a number of JavaScript based frameworks that I was interested in familiarizing myself with for future use.

I started development with audio analysis. I found that EssentiaJS had a number of helpful analytical models for my analysis. Implementation proved relatively simple for some models and more challenging for others due to incomplete documentation, but in the end I was able to include several models which analyze BPM, label, and various musical and emotional qualia (such as “danceability” or “mood happy”).

I decided that I would get the actual song names from the video descriptions, as those are often included in this content and are more reliable than an analysis tool.

Next, I began implementation of visual analysis. My plan was to analyze two characteristics of the video:

- The facial expressions of the audience members

- The “motion” of the audience, representing overall energy

This analysis can only be effectively done from the front-facing camera angle. To account for this, I only considered shots in which faces were present.

I began by implementing face-api.js, a model for analyzing facial expressions. From this, I was able to retrieve the expression labels ‘neutral’, ‘happy’, ‘sad’, ‘angry’, ‘fearful’, ‘disgusted’, and ‘surprised’. Given the context, I figured that the expressions ‘happy’ and ‘surprised’ would typically represent a positive emotion, while the rest would likely represent neutral emotions (since people in club environments rarely express negative emotions). To derive the overall emotional valence of the group, I took the sum of the confidence values for the ‘happy’ and ‘surprised’ labels of each person detected and divided that value by the number of people, getting a representation of the average valence of the audience. This implementation went relatively, smoothly. However, the information it provided proved somewhat lacking in information due to the nature of these events-people often express much more with their bodies than their faces in these environments.

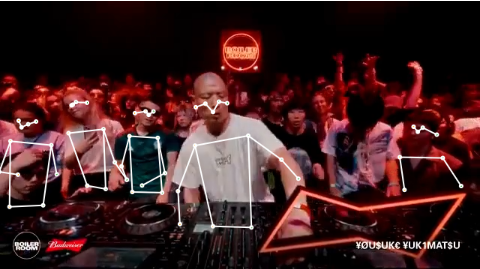

This led me to characteristic #2: motion detection. I first attempted to capture this using “optical flow” with oFlow. However, this did not work, mainly due to the dynamic lighting environment of the musical venues I was analyzing. Almost all flow was detected above the audience members, where white flashes streaked across the black ceiling caused by the strobe lights of the venue.

I considered attempting to analyze the motion of faces with the already-implemented face detection algorithm. However, I decided against this because of the way people in these environments tend to move their heads; “head bangers,” who move their heads up and down rapidly, often have their faces pointed at angles undetectable to the face-detection algorithm, leaving gaps in the analysis over time. These gaps would make it difficult to maintain the position of a specific face.

So instead, I decided to analyze the motion of the poses of audience members. I used the PoseNet model for pose detection. Even though it is more reliable, the gap problem does persist with poses, so I had to come up with my own solution for tracking them.

For those interested, here are the steps of my solution:

- Convert the current poses and previous poses into a 2d array containing the distances between each current pose and previous pose. In this case, “distance” is the weighted average of the distances between 13 of the 17 key points in the poses, each weighted by the confidence score of the pose with the worse confidence score. We skip consideration of the knees and ankles as they are typically occluded in DJ set videos.

- If any row or column has all values above a set threshold, add a column or row of 0s respectively. This is meant to account for the situation that one pose is lost from detection and another different pose is found.

- Setup this array to be a valid entry to a balanced Linear Assignment Problem

- If the array is square, leave as is

- If there are more previous poses than current poses (rows than columns), add rows of 0s until they are equal

- If there are more current poses than previous poses (columns than rows), add columns of 0s until they are equal.

- Using LAP-JV, calculate the assignments of each pose according to the linear assignment problem.

- The resulting cost is the total movement that occurred. To get the average movement per person, divide by the number of people who were continuously detected.

This method proved slightly more effective than the last. However, it did not reveal quite what I wanted from the crowd’s energy. It was not able to effectively capture the energy shifts that are evident to the naked eye.

I intend to experiment with more methods of energy detection in the future so that more clear conclusions can be drawn. My next approach is to look into large language models, though this approach might risk inconsistency in results. In the meantime, I have compiled a dataset of audio analyses for public use.

You can check out the dataset here and try the tool for yourself here.

< back to posts